You can fool some of the people all the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can not fool all of the people all of the time.

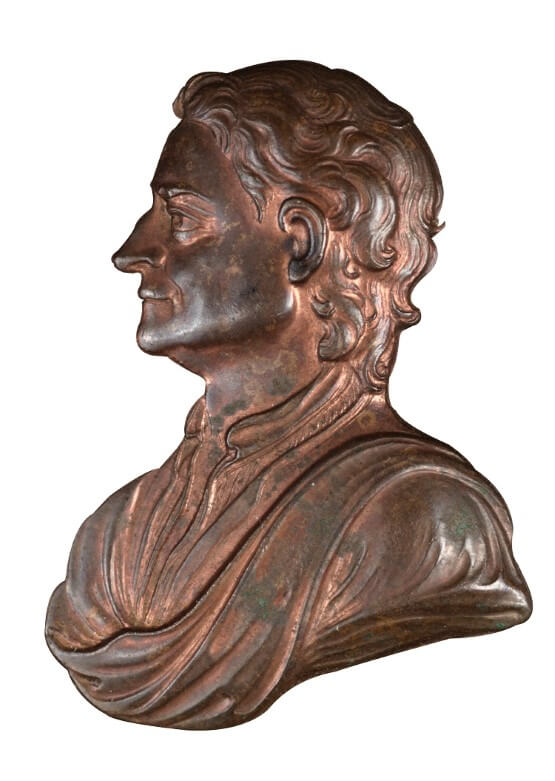

Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (in Encyclopedie, volume 4, 1754)

Many people see the current situation of the world as disastrous. Multiple wars play out as out a clear threat of the climate crisis caused by the industrial revolution looms over us all. Dark days indeed. Is there any light to be seen? Perhaps none, some believe. Perhaps the world is doomed to a 4 Celsius rise in temperature, a catastrophic displacement of several billion people as they move away from seas and the tropics, and a collapse of the current civilization. But perhaps there will only be a 3 Celsius rise in temperature, and there will only be massive wars and genocide with a remnant of today’s capacity hoarded by a few. Or maybe, we can halt the rise in temperature at 2 Celsius. Maybe we can green our cities to give a milder microclimate, fill them with basin sponges to soak up floodwaters, and survive without our politics becoming ever more warlike and xenophobic.

I kept noticing the open society of Kazakhstan as we travelled through the country. Like many Asian countries which had to rebuild themselves after a period under foreign control, Kazakhstan has turned into an inclusive society. There is no state religion, and 137 different ethnicities following 46 different religious doctrines live together. People on the streets were extremely welcoming, and sometimes stopped to chat even though their command of English only mildly exceeded our knowledge of Kazakh or Russian. It is often hard for Indians to grasp how effective a cultural ambassador Bollywood movies have been. The movies had taken the message of our open polity across a vast spread of cultures.

I found a second reason for hope when I realized that low-tech and shared resources remain popular even in a petrostate like Kazakhstan. There are certainly BMWs and Mercs on the streets, but you can also find buses and bicycles. There are metros in the cities and also free kick-scooters which you can pick up at one place on the road and leave elsewhere when you are done with it. The world is already hotter than we wanted, but it is still possible to prevent 4 Celsius of heating. All it requires is cooperation and sharing.